Introduction

In the updated roadmap shared in early January 2026, Vitalik Buterin predicts that between 2027 and 2030, the primary method of validating blocks on Ethereum will shift from each validator re-executing every transaction to verifying cryptographic proofs sourced from zkEVMs. This approach aims to enable capacity increases with higher gas limits during the same period, positioning itself as an architectural transformation that maintains the balance of scalability, security, and decentralization at the protocol level. The Ethereum Foundation’s Shipping an L1 zkEVM series also grounds this vision in technical terms with the idea of having a limited number of proof producers generate proofs and all validators perform low-cost verification, rather than spreading the execution cost across the entire network.

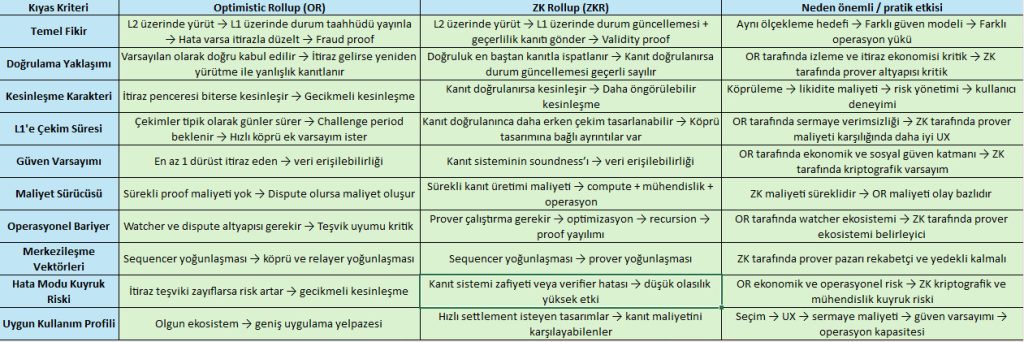

The Difference Between Optimistic Rollup and ZK Rollup

The distinction between Optimistic rollup and ZK rollup in Layer 2 scaling architecture is fundamentally based on the trust model between error detection and proof of correctness. In the Optimistic Rollup approach, L2 transactions are executed off-chain and state updates are sent to L1, but these updates are assumed to be correct and can only be challenged with a fraud proof if someone claims they are incorrect. Therefore, in a typical design, withdrawals from L2 to L1 are delayed due to the challenge period, and in practice, this window is set to days. The ZK rollup approach, on the other hand, aims to prove the correctness of the state transition on L2 with a validity proof verified on L1. In this model, finality is more directly dependent on the verification of the proof, so withdrawal delays and liquidity costs may be better than in the optimistic design, but the price is the complexity and cost of proof production.

Source: Darkex Research Department

Why Data Availability is a Separate Security Layer

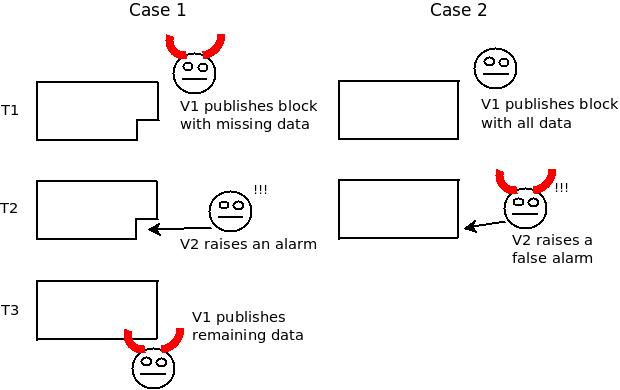

Fraud proof or validity proof models solve the proof of correctness problem. However, data availability is a separate security layer. Even if a block producer provides a mechanism proving the transition of state, if it does not publish the entire block data, validators cannot reconstruct this transition and the system effectively stalls. This situation leads to the network becoming functionally unusable, despite the fact that validity can be theoretically proven.

Source: “github.com/ethereum/research/wiki/A-note-on-data-availability-and-erasure-coding/52e1d03b0254cded8b67105be17ba9890b7ad8d3”

This diagram shows that data withholding and false accusation scenarios become indistinguishable from an external perspective beyond a certain point. Even if the data is genuinely withheld, or if a malicious actor generates a false accusation, both situations are observed identically at the protocol level.

Source: “github.com/ethereum/research/wiki/A-note-on-data-availability-and-erasure-coding/52e1d03b0254cded8b67105be17ba9890b7ad8d3”

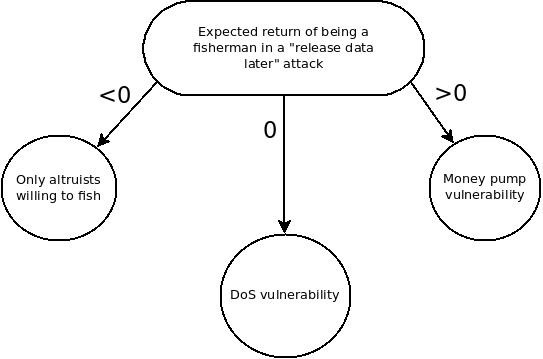

Therefore, attempting to incentivize data availability through alarm-triggering actors creates a structural dilemma. If the reward is positive, the system becomes vulnerable to pump-and-dump schemes; if the reward is zero, the risk of free DoS arises; if the reward is negative, security is left to altruism. This dilemma shows that the data availability problem cannot be solved by incentive mechanisms alone. On this basis, the ETH roadmap addresses cryptographic approaches such as erasure coding and probabilistic sampling as part of the base layer security to ensure data availability.

Why Does Vitalik Predict That zkEVMs Will Be the Primary Method for L1 Block Verification?

Vitalik’s emphasis on zkEVMs becoming the primary method by which validators validate L1 blocks is not just about L2 preferences, but a claim that directly redefines L1’s validation cost. In today’s model, L1 security is ensured by validators re-executing transactions within the block, which is one of the fundamental bottlenecks preventing gas limit increases. In the L1 zkEVM vision, however, the network verifies execution correctness through proof verification rather than re-execution. This theoretically reduces the CPU and time budget per validator while enabling the safe targeting of higher block capacity. Therefore, Vitalik associates the 2026–2028 transition steps with adjustments to gas pricing and execution data structures, and the 2027–2030 range with proof verification becoming the dominant model. The critical distinction here is that as validation becomes cheaper, proof production becomes a new system role, and the success of protocol design becomes dependent on how this role scales and distributes.

Positive and Negative Outcomes

On the positive side, the strongest outcome is that the gas limit increase becomes a more manageable risk profile as the validation burden shifts to proof validation. This is a strategic lever for mitigating congestion and fee shocks during high-demand periods, targeting more transactions and higher bandwidth on L1. The second positive outcome is that the fixed cost of validation work on the validator side makes node operation and validator operations more accessible, which is consistent with the goal of decentralization. The third positive outcome is the standardization of the concept of provable execution at the protocol level, along with the strengthening of the verifiability layer.

The most critical risk on the negative side is that proof generation may require specialized hardware and expertise in practice, potentially leading to centralization of provers. If verification becomes cheaper while proof generation remains expensive, a small number of professional operators could dominate proof generation, creating a new vector for centralization in terms of censorship resistance and liveness. The second negative area is system complexity. The goal of L1 verification with zkEVM opens up new design axes such as recursion architecture, proof size budget, P2P proof propagation, and client compatibility. If these axes are not managed correctly, low-probability but high-impact tail risks, such as accepting incorrect proofs from a security perspective, and consensus-class risks, such as inconsistent verification between clients from an engineering perspective, increase. The third negative area is incentive and cost distribution. If it is not clear who bears the prover cost, how provers are rewarded, how competition is sustained, and how redundancy is guaranteed, the new verification model may settle into an economically fragile equilibrium. Therefore, the Ethereum Foundation’s milestones focused on achieving mainnet-grade security by 2026 are not merely cryptographic details but core requirements that determine the feasibility of the 2030 vision.

Conclusion

The framework outlined by Vitalik Buterin for the 2027–2030 period is a protocol-level architectural transformation that aims to shift the primary cost limiting Ethereum’s scalability from execution to validation. The trade-off between delay and proof cost created by the differences between optimistic rollups and ZK rollups in L2 is now being transferred to L1 block verification and attempted to be solved with zkEVM. In a successful scenario, the reduction in verification cost could support the decentralization goal through validator accessibility while combining higher capacity with a better fee regime. In a risk scenario, however, prover centralization, proof architecture complexity, and vulnerabilities in incentive design create new systemic risks. Therefore, the practical implication of the claim that “zkEVMs will become the primary method by which validators validate L1 blocks” is not just speed, but also the decentralization of proof production and a provably higher cryptographic security threshold.

Disclaimer

All information on this website is provided for general informational purposes only. We make no warranties regarding the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the content.